Given the substantial increase in the money supply in the US in recent years, concerns over its impact on inflation are understandable. We delve more deeply into this connection and find cause and effect is not quite that straight-forward.

More money, more inflation?

The dramatic increase in the money supply over the past year has been the poster child for those who worry about easy monetary and fiscal policies driving high rates of inflation. Both the narrow M2 measure and the broader Divisia M4 measure reached levels this year they did not see even in the 1970s.

Fed’s M2 and Divisia M4 excluding USTs money supply, Y/Y

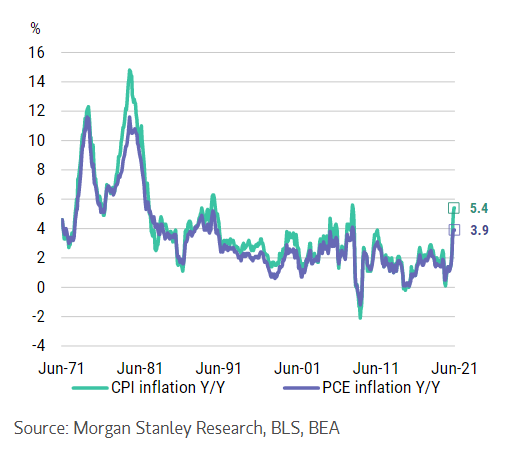

Meanwhile, inflation has surprised to the upside in three consecutive monthly reports this year.

Headline CPI and PCE Inflation, Y/Y

Case closed? Not quite.

The world has changed since the 1970s

Most students of economics learned about the monetary system that existed under the gold standard. But some concepts don't apply in a ‘modern monetary system’ like the one that exists today.

Under a fractional reserve banking system, banks needed base money in order to lend. The impact of an increase in base money was multiplied as banks lent that money – this is known as the ‘money multiplier’ effect.

But that system no longer exists in reality. Banks don't require reserves in order to lend. Banks can make loans – which become assets of the bank – by simply creating a deposit liability on their books, ie crediting the bank account of the borrower.

The nonexistence of the ‘money multiplier’ explains why quantitative easing (QE), ie the creation of base money, has not led to inflation. However, the recent increase in the money supply was not entirely driven by QE.

What drove the money supply higher?

While we can deny the money multiplier, we can't deny that the money supply increased dramatically over the past year. So what drove it higher? Larger government deficits have certainly played an important role.

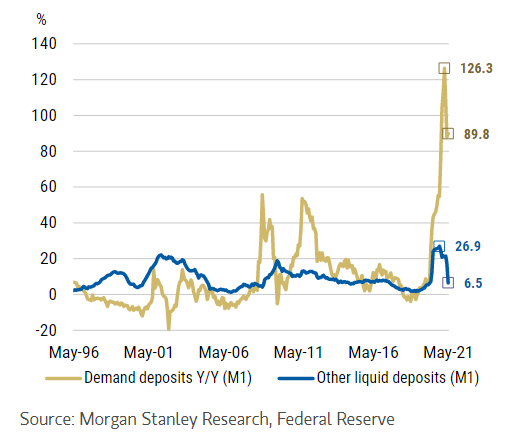

Currency in circulation also increased notably over the last year relative to history. But currency growth paled in comparison to the growth rate in demand deposits. And even the growth rate of other liquid deposits – which rose notably as well – didn't hold a candle to the growth in demand deposits.

Demand deposits Y/Y and other liquid deposits Y/Y (both in M1)

The important question for inflation is how are those demand deposits being used?

First, we can look at what the banks do with them, ie what assets do banks hold against the deposit liabilities. Second, we can look at how consumers are spending money, which they presumably withdraw from deposit accounts to settle payment.

In the past, most deposits in the banking system were connected to loans. From the early 1990s to November 2008 – before the Fed began quantitative easing (QE) – loans and leases offset 92% of deposits on average.

Since the advent of QE, loans and leases have offset 77% of deposits on average. And today, loans and leases offset only 61% of deposits. What assets have made up this difference since November 2008, and more recently since February 2020?

In the six years post-GFC, cash assets offset nearly the entire decline in loans/leases as a percentage of banking deposits. This QE-driven increase in cash assets is unlikely to prove inflationary, in our view – similar to post-GFC.

Our analysis of the money supply thus far has led us to conclude it will be much less inflationary than feared. However, we have yet to discuss the consumer side of the equation, which is important for how inflation has evolved, and will evolve.

Money in the hands of consumers

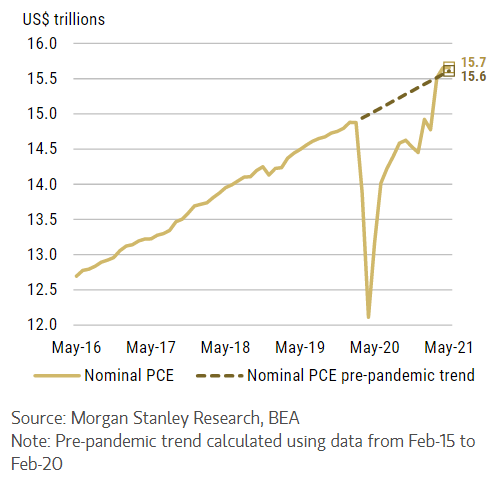

How are consumers spending the money that ended up as demand deposits? And how has it impacted inflation? Consumers haven't been shy about spending money over the past year, but they haven't spent nearly the amount that has piled up as demand deposits. Deposits are running US$3.3 trillion above the pre-pandemic trend, while personal consumption is running in line with the trend.

Demand deposits Y/Y and other liquid deposits Y/Y (both in M1)

US nominal personal consumption expenditure (PCE) vs pre-pandemic trend

Our economists have suggested excess savings will rise to US$2.3 trillion before a modest drawdown begins in 4Q21. The divergence between deposit growth – way above the pre-pandemic trend – and personal consumption – back to trend – supports their view that excess savings won't be drawn down significantly in the near future.

This divergence between deposits and spending has important implications for inflation – as the money supply by itself is not inflationary unless someone uses the money to spend. It's the demand generated by spending relative to the supply available for sale that can send prices higher or lower.

Where money is being spent

What have consumers been spending money on, after adjusting for inflation? US consumers have spent money on durable and non-durable goods well above their pre-pandemic trends. Meanwhile, real spending on services is running well below its pre-pandemic trend.

The substitution away from services and toward goods has been a defining characteristic of the pandemic.

While there has been signs prices have risen most where spending has been highest: on durable and non-durable goods. However, prices have also risen for services – where spending has lagged its pre-pandemic trend. As a result, we find it hard to conclude that the dramatic increase in the money supply drove inflation higher. Rather, higher consumer prices have been driven more by supply shortages. In the case of services, labour supply shortages are to blame. In the case of durable goods, it has been the result of unprecedented consumer demand substitution between goods and services.

What to watch for

In conclusion, we suggest focusing on supply chains and consumer behaviour – instead of the growth rate of money supply, now in free fall – for a better read on inflation dynamics.

In that regard, the past behaviour of consumers raises questions, some of which raise doubt about the sustainability of higher rates of inflation. For example:

- Won’t brought-forward spending on durable goods – which last a long time – reduce future consumption on durable goods much more than on non-durable goods, which don’t last long?

- Now that more people have motor vehicles and recreational vehicles, won’t they spend less on transportation services now?

- If you made your home a nicer place to be with durable goods, won’t you spend less on services outside the house than you used to, and also spend less on durable goods for your house in the near future?

- If you learned that nondurable goods can be just as good as services, won’t you continue to substitute away from services?

- If you are going to spend more on recreational services outside the house now, aren’t you going to reduce spending on recreational durable goods, especially since you already bought them and they are durable?

Some of these questions – which will only be answered over time – hint at a larger downside risk for spending on durable goods than an upside risk for spending on services. And since the actual spending increase on durable and non-durable goods relative to the pre-pandemic trend (US$550bn) was nearly the same as the actual spending decrease on services relative to trend (US$508bn), downside risks to consumption abound.

For a copy of our full report, speak to your Morgan Stanley financial adviser or representative. Plus, more Ideas from Morgan Stanley's thought leaders.